By Chris Manganiello

The year 2021 was a big water year for Alabama, Florida and Georgia, and the so-called “water wars.” Georgia walked away with most of the spoils.

In January, the state of Georgia and the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers (Corps) finalized a perpetual contact for access to storage space in Lake Lanier.

In April, the U.S. Supreme Court issued a final opinion in the Florida v. Georgia legal case; Florida lost.

In August, a federal judge rejected a lawsuit claiming that the Corps did not follow proper procedures when preparing the Apalachicola-Chattahoochee-Flint (ACF) Water Control Manual. The suit has been appealed to the 11th Circuit of Appeals.

What’s at stake?

- Limited water resources will be further stressed by growing populations, expanding economies, extreme weather, and climate change.

- Water in the Chattahoochee River basin for more than five million people – homeowners, businesses, and communities of all sizes from Helen, Georgia, to Gordon, Alabama.

- About 800,000 acres of irrigated agriculture in Georgia’s portion of the Chattahoochee and Flint River basins, and a big slice of Georgia’s $13 billion farm gate value of all food and fiber commodities grown in-state.

- Historic tupelo honey industry in the Apalachicola River’s floodplain and Apalachicola Bay’s oyster fishery.

- Millions in recreation dollars generated on Lake Lanier, in the Chattahoochee National Recreation Area, at Columbus’ whitewater course, and in the sport fishing industry.

- Water necessary for energy generation and industrial production.

History of the Dispute

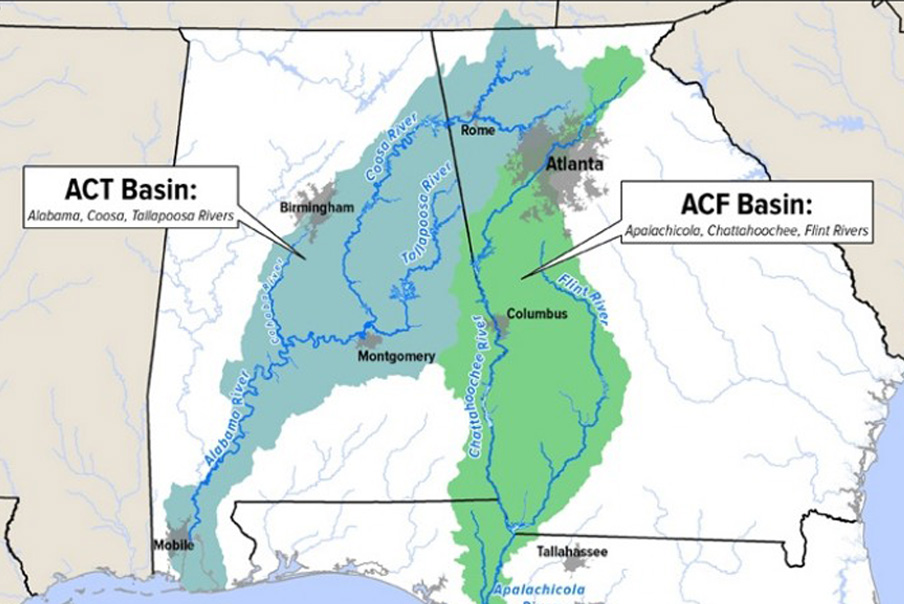

Since the 1990s, Georgia, Alabama, and Florida have fought over the use of water in the Apalachicola-Chattahoochee-Flint River Basin (ACF), which is heavily influenced by the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers’ operation of Lake Lanier’s Buford Dam and four other similar dams. Lake Lanier lies within the Chattahoochee’s headwaters, just north of Atlanta.

The Corps built Lake Lanier in the 1950s with clear Congressional authorization for flood control, navigation, and hydropower. Over time, however, Lake Lanier has become the primary source of drinking water supply for metro Atlanta, and Alabama and Florida have argued that Georgia withdraws too much and isn’t sharing the water fairly. All three states have turned to the courts to try to resolve the conflict. Key litigation and policy decision milestones include:

- In 2009, a federal district court judge ruled against Georgia, deciding that water supply was not an authorized purpose of Lake Lanier. The judge gave Georgia three years to reach a water–sharing agreement with Alabama and Florida and to get Congressional approval.

- In 2011, the Eleventh Circuit Court of Appeals reversed the 2009 district court decision, ruling that water supply is an authorized purpose of Lake Lanier, on par with hydropower, navigation, and flood control. Furthermore, the appeals court gave the Corps one year to determine the extent to which it could operate Lake Lanier to meet water supply needs in addition to the other authorized purposes.

- In 2012, the Corps responded to the 2011 Eleventh Circuit decision, determining it has discretion to operate Lake Lanier in order to meet Georgia’s current and future water demands.

- In 2013, Florida filed an original jurisdiction action against Georgia in the U.S. Supreme Court, alleging that Georgia’s unreasonable use of water in the Chattahoochee and Flint rivers had impacted the Apalachicola River, damaged the oyster ecosystem, and harmed Florida’s economy. This was the beginning of Florida v. Georgia (no. 142).

- In 2017, the Corps released an updated ACF Water Control Manual to guide operations of the Corps’ five reservoirs, dams and navigation locks in the basin to meet Congressionally authorized purposes of power generation, flood control, navigation, water supply, recreation and fish and wildlife. This manual had not been updated since 1958.

- In 2017, the State of Alabama and the National Wildlife Federation et. al. filed separate legal challenges against the Corps, alleging that the Corps did not follow National Environmental Policy Act (NEPA) procedures when revising the Water Control Manual.

- In January 2021, the state of Georgia and the Corps finalized a $70 million perpetual contact for access to storage space in Lake Lanier – or a bucket in a bucket – for 254,170-acre feet and up to 222 million gallons of water per day. This contract does not guarantee that the water will be there, just that the state has access to storage space. By 2023, Georgia developed individual sub-contracts with the Lake Lanier’s five water utilities. It is worth noting that the contract is based on now outdated and inflated need and population projections through 2050. This means there may actually be enough water to meet demand well past 2050, and thus the now abandoned Glades Reservoir is unlikely to get built in the future.

- In April 2021, the U.S. Supreme Court issued a final opinion in the Florida v. Georgia legal case that began in 2013, in which Florida claimed Georgia unreasonably overconsumed Chattahoochee and Flint River water to the detriment of the Apalachicola downstream. In plain terms, the court dismissed Florida’s claims. In a 9-0 opinion, the court determined that Florida failed to make a compelling legal argument and failed to provide sufficient evidence that Georgia uses too much water or that any harm to Florida’s oyster population could be traced to water use in Georgia. You can read the opinion here.

- In August 2021, a federal judge rejected the lawsuit lodged by Alabama and the National Wildlife Federation et. al. claiming that the Corps did not follow administrative procedure or fully comply with other environmental laws when preparing the Water Control Manual that governs the operations of Buford Dam/Lake Lanier, West Point Dam/Lake and the three other federal dams in the ACF. In 2023, the National Wildlife Federation et. al. appealed the decision to the 11th Circuit Court.

- In August 2021, the Corps made a decision with repercussions for Lake Lanier and the Chattahoochee River. The Corps approved a new water supply accounting policy that will allow public water managers to credit “made inflow” into Corps reservoirs from an upstream reservoir and/or wastewater treatment plants. This new policy will undoubtedly be applied to Lake Lanier. While the new policy makes sense from a water volumetric perspective, this new accounting system could reduce flow downstream of Buford Dam, particularly during drought.

What Does CRK Think?

CRK has always advocated for what is best for the river and the people who depend upon it, regardless of political or jurisdictional winners and losers in the water wars. CRK believes Alabama, Florida, and Georgia must negotiate an interstate compact to equitably divide the waters. Furthermore, climate challenges – not legal challenges – should drive collaboration and equitable water management decisions.

With the U.S. Supreme Court case out of the way, CRK looks forward to again advocating for a shared water plan like the one we helped develop with the ACF Stakeholders.

The three states can turn to an existing technical solution produced by the ACF Stakeholders—a collaborative group of agricultural, municipal, industrial, environmental, individual, and other interests who live, work, and use the water resources of the ACF river basin. Their Sustainable Water Management Plan (2015) offers recommendations to improve data collection and drought management; to alter operations of the Corps’ five dams and reservoirs; and to reduce water withdrawals while maximizing returns. The plan represents a technical solution formed from the ground-up where a top-down solution has been lacking.

CRK also believes there are two important things that Georgians and our downstream neighbors should take from the U.S. Supreme Court’s 2021 opinion in Florida v. Georgia.

First, the Justices emphasized Georgia’s “obligation to make reasonable use of Basin waters in order to help conserve that increasingly scarce resource.” This statement matters because Georgia argued that the state’s water use was reasonable. All the water conservation and efficiency work Georgia has done and that was cited in their legal arguments was indeed deemed reasonable. The Justices’ opinion also means those laws, policies, and tools are here to stay. There can be no major roll-backs in water conservation and efficiency policy in Georgia. There can only be roll-forwards, new strategies, and quantifiable demonstration of reasonable use.

Second, the most progressive acknowledgment in the Court’s opinion was that Georgia stated throughout the case that “climatic changes” are affecting our rivers. One of Georgia’s central arguments was that reduced river flows in Florida were not Georgia’s fault. It was drought, said Georgia, which has become more frequent and damaging. The Court accepted this argument.

CRK’s advocacy and the Court’s concluding statement align closely. Georgians have an obligation to conserve water. CRK’s Filling the Water Gap highlights many examples of success and opportunities to improve water efficiency and conservation in the basin. The state cannot keep growing without implementing progressive water saving polices in our cities, businesses and industries, or on our farms.

If a robust culture of conservation does not take hold and advance in metro Atlanta, the Flint River basin, and across all economic sectors, Georgians will be back in court again.

At the end of the day, meeting the challenges of climate change – not legal challenges – will drive our future water decisions.

Updated January 11, 2023. For more information about the tri-state water conflict and CRK’s efforts to resolve the dispute, email Water Policy Director Chris Manganiello or call (404) 352-9828.